Nazism opened the door to the global terrorism. It drew a structural evil where nobody was saved, not even the German people. The enemy: everybody who could think for themselves in a critical and creative way, everybody who didn't live according to the Nazi rules. The Aryans were just "manufactured individuals", designed to become dehumanized automatons. The socialization of the crime through violence turned into a culture was one of the main goals that Nazis managed to make in their camps and society.

This is a current book that reflects on the past and offers us questions on the present.

El nazismo abrió la puerta al terrorismo globalizado. Dibujó un mal estructural donde nadie estaba a salvo, ni siquiera el pueblo alemán. El enemigo: todo aquel que pudiera pensar por si mismo de una forma libre y diferente a lo que dictaban las reglas nazis. Los arios eran tan sólo "individuos fabricados", diseñados para la violencia, es decir, autómatas inteligentes deshumanizados. La socialización del crimen a través de la violencia convertida en cultura fue uno de los objetivos que lograron establecer en los campos y en la sociedad.

Un libro que pone al descubierto las cuestiones aún hoy más vigentes.

Book Review by Aida C. Rodríguez (University of Barcelona):

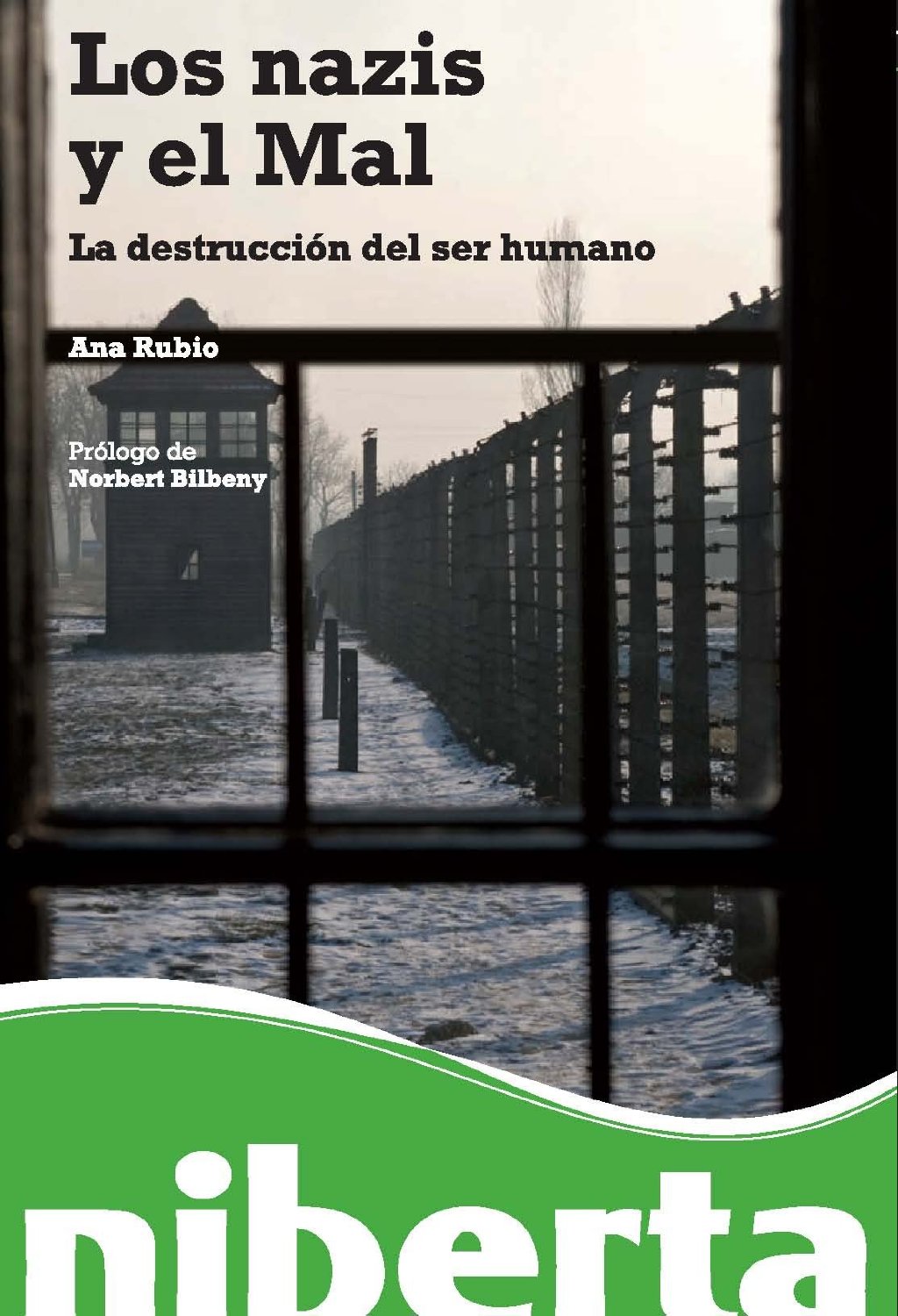

Although over seventy-five years have gone by since Hitler's rise to power in Germany, the topic of Nazism and the Holocaust is a still relevant one, keeping alive the questions: How could this have happened? And what are the consequences of what took place? These questions are broached in Los nazis y el mal, la destrucciσn del ser humano, published by Editorial UOC under the imprint Niberta and with a prologue from the Chair in Ethics at the University of Barcelona, Norbert Bilbeny. What is, at first, a very wide-ranging issue is pared down to an exhaustive investigation of the concept of evil in the men of the Third Reich or what is tantamount to the same, the process of how human beings become evil as embodied in the Third Reich.

The author, Ana Rubio-Serrano, holds a doctorate in Theology and a degree in Advanced Philosophical Studies, although her work mainly concentrates on her thoughts on Nazism and the Holocaust, subjects on which she speaks and writes articles for the media. In this book, we see how her research primarily focuses on the search for a response to the question concerning the nature of man where evil is concerned.

We might think that the topic of Nazism is already overloaded with references and that it would be difficult to add any new elements to the thinking on this matter. However, just a few decades represent a brief interlude in history as a whole and the complexity of Nazi evil continues to trouble us; above all, it is terrifying to be aware of the actual degree of evil achieved by people who, like us, lived in cultured and developed societies and were therefore presumably civilised, transforming their inheritance of erudite emancipatory rationalism into merely instrumental reason at the service of evil.

Indeed, after Nazism, the world asked, through the words of Adorno, how we should educate our children in order to prevent Auschwitz from being repeated. Undoubtedly, this is established as the primary objective for catharsis to begin. But the same question also comes under the umbrella of philosophy, art and government and they are all encompassed within one question: How should we understand our existence after Auschwitz? The world can never be the same again and the picture that the concentration camps in this Polish city drew still unsettles and disheartens us. We should not overlook the fact that other places before Auschwitz endured atrocities and that even since then human beings have continued destroying the lives of others in places like Siberia, Cambodia, Rwanda, Sarajevo and Palestine. It could be said that the symbol of Auschwitz and what it represents continues to appeal to us.

To illustrate her work, the author presents us time and time again with the writings and speeches of Hitler himself, analysing the theoretical construct that was to later gradually unfurl and be reproduced in German society. It is precisely this aspect that is the main original feature of Ana Rubio-Serrano's work.

Thus, the book starts by describing how Nazism introduced its power over German society through its very structure. The globalization of Evil is the first of the four parts into which the book is divided and in it, we essentially find a thorough description of the process of how society becomes evil, allowing us to talk about Nazi medicine, Nazi law, elaborate anti-Semitic racism, the religious dimension of Nazism or the Nazi use of language. We also read how in order to achieve its aims, Nazism knew very well how to bring together a variety of social frustrations - human miseries, we could even call them - to twist them to its benefit. Manufacturing a people, as Hitler planned, required deep planning and also a doctrine that would serve to resolve any doubts that existence entails.

The author's intention is, above all, to explore and separate the wheat from the chaff on the path towards evil, a path that ends in the destruction of the human being and starts in the creation of Nazi anthropology. As the author puts it in the second part of the book, globalization of the masses, this anthropology was able to produce a new race of dehumanised men and unquestionably left no aspect of individual and social human life to chance, defining in great detail the Aryan male as a finished product that does not need to change or evolve. This is how Nazi totalitarianism turned individuals into masses, dividing them up and classifying them in turn into the anonymous masses, or the people; the noble masses, who were the SS men and soldiers; and the surplus masses, which they made every effort to wipe out. Although each type can be differentiated from the others by its characteristics and functions, all three have in common the manipulation suffered, leading them to give themselves up, in one way or another, to the destiny that their mass-identity required, therefore causing the notion of the individual and his or her autonomy to disappear. The sacrifice of the individual in the name of the masses is a defining element of totalitarianism, as noted by Hannah Arendt in her work The Origins of Totalitarianism, which leads to the banalisation of evil, an idea that Arendt herself observed based on Eichmann's trial and which the author uses throughout her book. The further we become immersed in this banality the more we see how human evil becomes inhuman en route to a lack of conscience, with no going back. Dehumanised and transformed into part of a mass, victims and victimizers, there is nobody to appeal to who can help reconcile them, so they become natural enemies.

In the third part, "the consolidation of structural universal evil in concentrationary society" the matter is raised of the unique nature of Nazism which, in the author's view, does not revolve around its barbarism or the shocking number of victims that it left in its wake, but rather in how the process of the banalisation of evil and its global implementation within structures led to the dehumanisation of individuals in order to achieve an ultimate goal in which the idea of evil blossoms and takes on a specific form: Auschwitz and its realm. "The Holocaust was the architect of the biggest crisis that human beings have experienced throughout history: the crisis of faith" (p.149).

The last part of the book discusses "the globalisation of evil against the almighty God" to explain to us how faith in humanity and faith in God were quite frankly overturned by the horror of the extermination camps. Even so, in this landscape of evil we can still find the traces of humanity that thousands of people left behind to prove the existence of a form similar to that of the almighty which is the very antithesis to that imposed by the Nazis; it is transforming, human and compassionate, capable of catching the eye of another when he looks at it and recognises himself in it. This is why the last part of the book brings together the testimonies of victims and survivors who were there and discovered the almightiness of God.

El abogado defensor de Eichmann en el juicio de Jerusalén, el doctor Robert Servatius de Colonia declaró al encausado inocente de las acusaciones que le imputaban responsabilidad en “la recogida de esqueletos, esterilizaciones, muertes por gas, y parecidos asuntos médicos”, y el juez Halevi le interrumpió: “Doctor Servatius, supongo que ha cometido usted un lapsus linguae al decir que las muertes por gas eran un asunto médico”. A lo que Servatius replicó: “Era realmente un asunto médico puesto que fue dispuesto por médicos. Era una cuestión de matar. Y matar también es un asunto médico”

Desde los años 30 hasta finales de la Segunda Guerra Mundial el papel que jugaron los médicos de la Alemania del Tercer Reich fue de suma importancia para la planificación y el desarrollo del proyecto nazi de eliminación de la persona humana. Los asesinatos médicos que practicaron dichos doctores se asentaron sobre dos grandes fundamentos. El primero, el llamado “quirúrgico”, con el que se mataba a un gran número de personas por medio de una tecnología controlada como era el gas altamente venenoso que se suministraba a las víctimas en los campos de concentración a través de las duchas o a plena luz del día por carretera en furgones herméticamente cerrados.

| Language | Status |

|---|---|

|

French

|

Unavailable for translation.

Translated by Zaida Machuca Inostroza

|

|

Portuguese

|

Already translated.

Translated by João Romão

|

|

|

Author review: The translation was done quickly and accurately; the communication with João is excellent. Moreover, he has a great attitude and enthusiasm for the work. Highly recommended! |